As published by Nikkei Asia. Click here to read the original article.

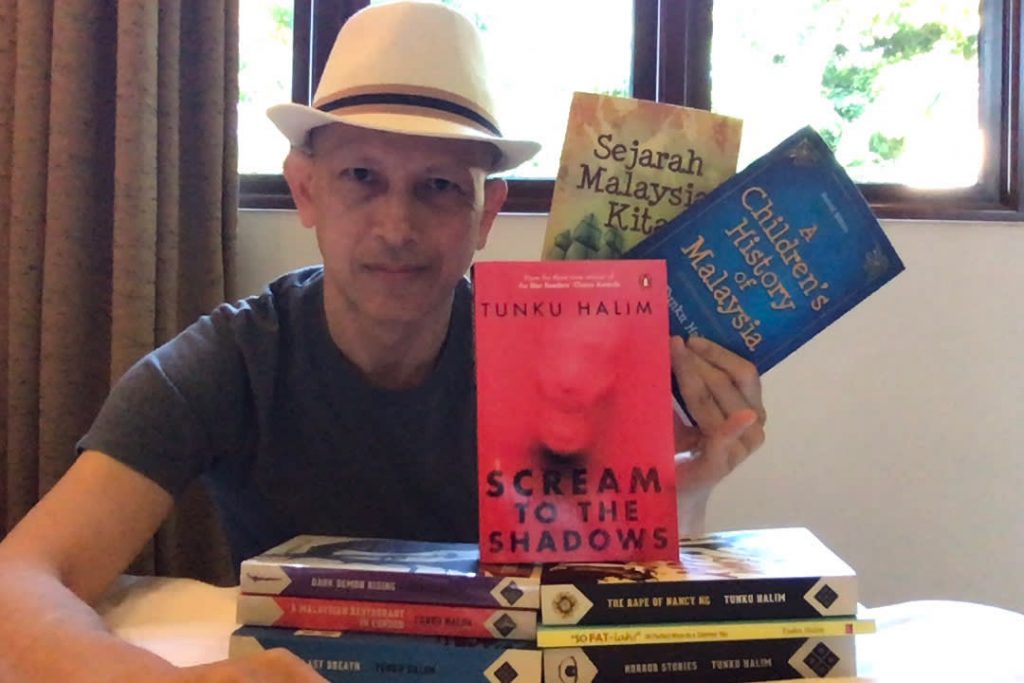

Tunku Halim brings ancient demons to life in contemporary fiction

KUALA LUMPUR — When it comes to harrowing, terrifying or dangerous places, Malaysia would hardly come to mind — even for veteran Asia watchers. Yet Tunku Halim, a renegade member of the royal family of the Malaysian state of Negeri Sembilan, has won an honored place for his dark fiction because, as he puts it, Malaysians “love to share and pass around our ghouls, ghosts and spirits.”

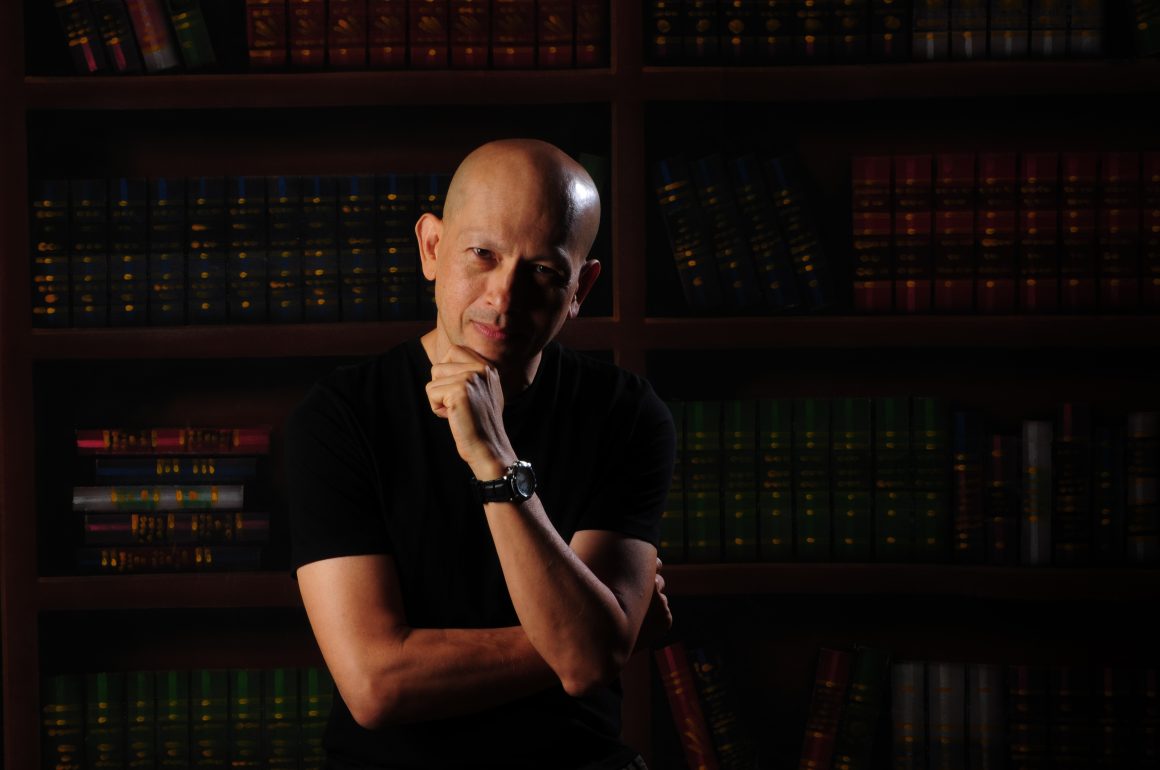

Tunku Halim bin Tunku Abdullah (Tunku is an honorary title) says he doesn’t feel comfortable with the term “horror,” preferring “dark” or “supernatural,” but he draws on a vast panoply of local myths and superstitions, and has often been called the “Malaysian Stephen King,” in a reference to the best-selling American horror writer.

His early work, repackaged with scary imagery as “Horror Stories” in 2010, remains among the best-selling volumes of English-language fiction in Malaysia, and Penguin Southeast Asia recently brought out a collection of the best of his short stories, appropriately titled “Scream from the Shadows,” attesting to his preeminent position as his country’s literary “Prince of Darkness.”

“But I don’t write for money, and certainly not for Western readers,” the 54-year-old lawyer insists. “When I mention a plate of nasi lemak (a fragrant rice dish cooked with pandan leaf) or the names of traditional demons, I assume a certain knowledge and familiarity. People think I’m drawing on imagination, but it’s more putting stories in the context of Malaysia — where everyone, educated or not, is part of a very superstitious lot. During our dinner parties, people will readily recite tales that would be scoffed at in the [West].”

Halim, who qualified as a barrister and studied shipping, trade and finance at London’s City University Business School, says he had no idea that he would eventually find himself invoking the deeds and misdeeds of the Orang Minyak, an oil-slathered beast specializing in the abduction and rape of virgins, or the Pontianak, a seductive female ghost known for disemboweling victims with her long fingernails.

“Dark tales, which embrace the paranormal, the mysterious and the supernatural, continue to be of interest because many of us find something lacking in our workaday world and in the routine of our existence,” he says. “These tales provide an intensity … of that ancient memory remaining in our DNA. So it is more than just escapism.”

A drawing of the Pontianak, a seductive female ghost known for disemboweling victims with her long fingernails. (Courtesy of the author)

His writing talents emerged when, working for a large developer in Kuala Lumpur, he tried to describe a winding road between suburban divisions that many considered to be haunted. Later, he moved to Australia for two decades, doing legal work for the American computer technology company Oracle before fulfilling a dream to live on the island of Tasmania.

“Funny, I was never afraid of anything in Australia, no matter how isolated,” he declares. “But as soon as I came back to Malaysia, I got scared just to be in the house alone.”

Drawn back to Malaysia, in part, by the “bright period” that followed a rare change of government in the country’s 2018 general election, Halim says he has been disappointed by the subsequent collapse of the reforming administration that briefly held power. But, he says, his return has rejuvenated his aim of capturing Malay folklore, legends and history for those who do not read the Malay language.

Halim is most proud of his self-published “Children’s Encyclopedia of Malaysian History,” a five-year labor of love that included providing illustrations and graphic designs, and his novel “Last Breath,” in which he “explored the craft” more than worrying about entertainment value. The book is also a satire on the internecine world of Malaysian politics, where all the chronic problems of the country have been caused by an invented new ethnic group called the “dolops.”

“He captures the tension between our modern veneer and premodern beliefs quite well,” says his publisher, the writer Amir Muhammad, who is also the founder of the independent Malaysian publishing house Buku Fixi. Amir adds that Halim is “probably the most popular local fictionist who writes primarily in English.”

The author has not been bashful about attempting various forms of nonfiction. His first effort was a how-to book on purchasing condominiums in Malaysia, and he has also branched out with a volume of diet advice, “So Fat Lah!” In addition, he writes the blog Write, Lah!, and is working on an argument for the minimalist lifestyle, including how he moved from one country to another with only two suitcases of belongings. He defines “decluttering” as liberating, especially when it comes to “the madness of mobile phones.”

While some criticize his stories as formulaic, professor Malachi Edwin Vethamani, head of the English department at the Malaysian branch of Nottingham University, notes, “He’s really the leading figure in what’s known as Malaysian Gothic literature. And it’s not only that he’s part of popular culture, and such a suave gentleman, but he does push the genre into humor and satire and draws so well on the curses and cures of the bomoh, our medicine man, who is so intrinsic to Malay society.”

“Funny, I was never afraid of anything in Australia, no matter how isolated. But as soon as I came back to Malaysia, I got scared just to be in the house alone.”

Tunku Halim, on the power of superstition in Malaysia.

Halim, who cultivates a dapper and mischievous image and relishes his freedom to delve into whatever subject takes his fancy, says that writers “are looked upon as quite strange and different” in Malaysia. “Usually I’m just asked what magazine I work for and how much I earn. So when I give workshops, I just tell my students to think of writing as a very inexpensive hobby.”

He says he has no worries about censorship, which continues in Malaysia in spite of constitutional guarantees of free speech — Malaysia was ranked 101st of 180 countries in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index produced by Reporters Without Borders, a journalists’ organization. However, he does have occasional concerns for the reputation of his powerful family, among whom, he quips, “I’m still something of a novelty.” Halim tried to capture his admired father — a leading politician and founder of Malaysia’s Melewar-MIG manufacturing group — in the biography “Tunku Abdullah — A Passion of Life,” published in 1998 and revised as “A Prince Called Charlie” in 2018.

In the footsteps (or bloody footprints) of Stephen King, Halim hopes by next year to complete and unveil a long-running trilogy of “dark fantasy.” But he modestly downplays his lasting influence. “I don’t think I’m helping to preserve anything by putting our traditional spirits on paper,” he says, “when today’s young people know them very well, fear them and speak of them often.”

For readers, though, Halim’s fiction does seem destined to endure. As Amir puts it, his works “show that mankind does not survive on reason alone … that there are things unseen that are beyond our control, watching over us and maybe holding us to account when we’ve been bad.”

Leave a Reply